On Tuesday evening, several buildings on the Lewis & Clark undergraduate and graduate campuses were vandalized. The tags came in response to Indigenous Peoples’ Day, which is a holiday that occurs on Oct. 10 and is recognized by the state of Oregon.

LC students and staff awoke the following morning to find various buildings tagged with large messages written in graffiti. This is not the first time campus buildings have been tagged with similar messaging and iconography on Indigenous People’s Day, previously known in Oregon as Columbus Day. Previous instances have occurred on Jan. 25, 2021 and Oct. 11, 2021.

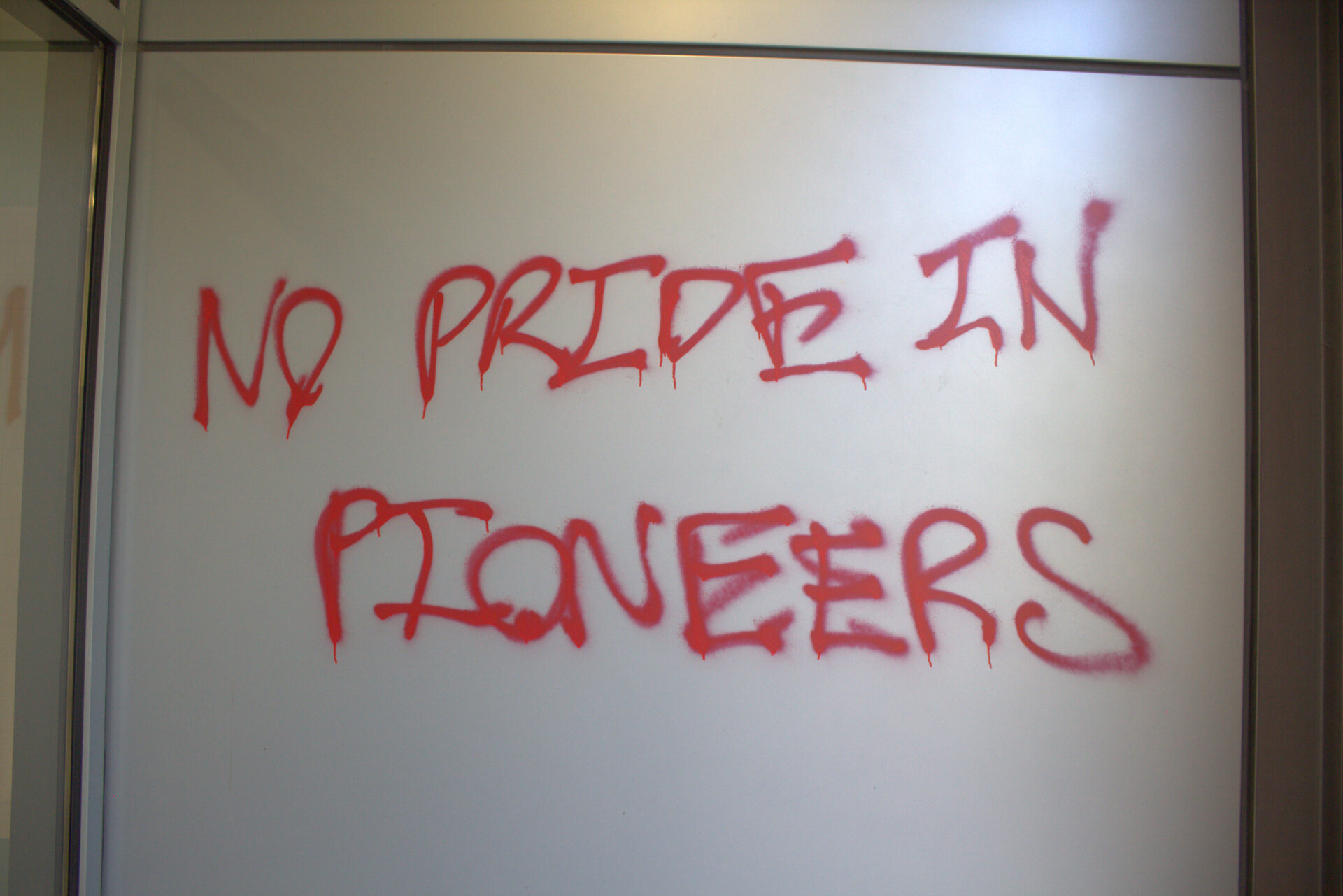

Across the front facade of J.R. Howard Hall read “CHANGE NAME” in spattered white paint that reached approximately a story tall. Multiple smaller messages written in red spray paint located on a front-facing windowsill and on the inner walls of the front doors read “DAY OF RAGE,” “LAND BACK” and “NO PRIDE IN PIONEERS.”

Along the side of BoDine Hall that faces the academic quad, “FUCK L+C” was written in the same tall white paint.

According to an email sent out to students and staff on Wednesday afternoon by Vice President of Student Life and Dean of Students Evette Castillo Clark, the York Graduate Center located on the graduate campus was also tagged. The school has not yet identified the persons responsible for the tags.

Dozens of students stood in front of the Howard steps during passing periods. Among them was Fabian Guerrero ’22, who said that he is not as upset about the tags as others seem to be.

“I support the name change,” Guerrero said. “The means to do so will never be completed through the avenues this college has taken.”

Guerrero was part of the committee that wrote the bill changing the name of the Associated Students of Lewis & Clark (ASLC) to the Associated Student Body (ASB), after which KPH, the school’s radio station and The Mossy Log followed suit. As he remembers, students responded by dropping ‘Lewis & Clark’ and ‘pioneer’ from the names of their own independent organizations, but the college’s name still remains.

“We were only able to do things that we could change, but that kind of voice only goes so far,” Guerrero said. “And then every year, all of a sudden this comes to life in a very physical and inconvenient way.”

Kaya Tsabari ’24 has seen three tags during her time at LC. She feels that the message of the tags gets bigger and bigger every year, but she cannot trace any effectual change among students or administrators.

“This has happened multiple times before,” Tsabari said. “The dialogue only stood for maybe a week or two and went back to nothing.”

According to Tsabari, the tags have divided students into three camps: those who do not support or are indifferent to changing the school’s name, those that support changing it and those that, while supporting the name change, would rather see effort and money spent toward creating scholarships or new programs for Indigenous students. Tsabari aligns herself with the third camp.

“I think that would be more beneficial than changing the name,” Tsabari said.

A team of workers from an independent contracting firm already working on-site, Technical Waterproofing, Inc., arrived at J.R. Howard Hall with a power washer around 1 p.m. on Wednesday. Tim Rea, the firm’s superintendent, said the taggers likely used a Super Soaker to spray the white paint, which would explain the tags’ size and splattered lettering.

According to Rea, the contractors will be using “nontoxic biodegradable removers made with soy” to remove the tags.

Around 4 p.m. on Wednesday, Clark sent out an email to the LC community. Clark said that the graffiti ran counter to “our institutional commitment to collaborate, engage, and dialogue as ways to advance our equity and inclusion goals.” Clark’s email also suggested that the tags may be shocking and “particularly retraumatizing for our Indigenous community members.” Director of the Indian Law Program Dr. Carma Corcoran is part of the Chippewa-Cree Tribe. She said that she was not surprised by the tags and understands that it is a form of protest where people feel as though they are not being heard.

“The statement that seeing the tags may be emotional and shocking, particularly re-traumatizing for indigenous community members, I as a Native American, as somebody who knows and uses trauma informed care, I don’t think that statement itself really speaks to indigenous people,” Corcoran said. “I would argue that it may be traumatizing for those that are not indigenous because truth telling is hard in this country.”

Clark’s email also received blowback from students online.

“So, harmless, frustrated, WARRANTED graffiti,” Caitlin Chow-Ise ’23 said in an Instagram story. “I think the white student body and us other POC will survive.”

The Native Student Union (NSU) Co-Leaders Annabelle Rousseau ’23 and Jenn Sosa Ramírez ’23 said that they do believe in the message of Land Back and changing the name of the school. However, they want to focus their attention on supporting the Indigenous community on campus. They also said that they do not hold all the answers or speak for all Indigenous people, and they also did not feel comfortable speaking for the native tribes of Oregon, as they are not descendants of those tribes.

On Oct. 10 before the graffiti was done, President Robin Holmes-Sullivan sent out an email to the student body addressing the recognition of Indigenous People’s Day.

“At Lewis & Clark we honor this day by recognizing the rich diaspora of Indigenous communities throughout the U.S., in Oregon, and locally that are diverse in history, culture, and pride,” Holmes-Sullivan said. “We owe First Peoples a great debt of gratitude for the countless social, historical, cultural, technological, and industrial contributions they have made to our country and the world. We also owe them an open acknowledgment of the generational harm done to their communities when the U.S. government forcibly removed their ancestors from their traditional lands.”

Holmes-Sullivan also announced that she met with a group of Indigenous alumni from diverse tribal backgrounds to discuss helpful and meaningful actions. The group wanted to start developing a formal relationship between LC and the nine federally recognized confederated tribes of Oregon as well as establish an educational program focused on studying the history of Indigenous peoples who originally occupied the United States.

They also want to create programs for new students to learn about LC’s history, focusing on the contributions and impact on Indigenous communities, as well as establish a scholarship program for students from Oregon’s federally recognized tribes.

Co-leaders Emi Olson ’23, Liese Baker ’23, Alaryx Tenzer ’23 and Gwenn Jergens ’23 of Students for Transformative Action, Abolition and Resilience (STAAR, previously known as the Prison Abolition Club) released a statement late Wednesday night urging students to not report the persons responsible for the tags.

“The discussion should be around the meaning behind the action and not who did it,” the statement said. “Please remember that protest can take many forms, including graffiti.”

In the past couple of years, LC students have taken a stance on changing the name of the school. Many different associations on LC’s campus have changed their own names to reflect their solidarity with the request.

“We appreciate that the admin is actively working towards creating scholarships for future indigenous students. However, a name change would go a long way,” Rousseau and Ramírez said via email.

“It’s really easy to see things as good or bad, legal or illegal and I acknowledge that the graffiti is an illegal act under the law.” Corcoran said. “But I think we have to take into consideration the human factor of it is an act of being heard. It is an act of protest. While we don’t have to agree with it, I think we acknowledge it as such, it is really important.”

Subscribe to the Mossy Log Newsletter

Stay up to date with the goings-on at Lewis & Clark! Get the top stories or your favorite section delivered to your inbox whenever we release a new issue.

Leave a Reply