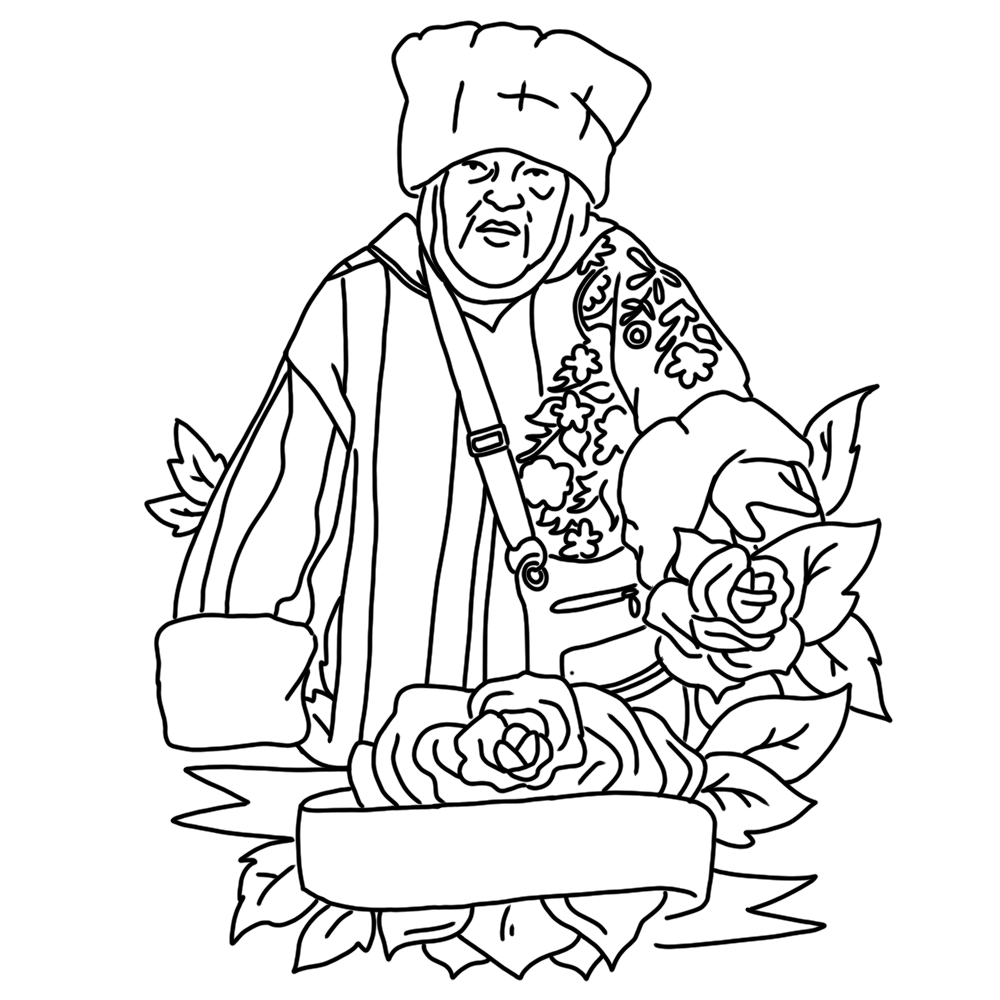

She first appeared online in November 2019, pictured standing on a New York sidewalk in a faux-fur coat she had made herself. She had been photographed by Brandon Stanton, creator of the massively popular blog Humans of New York, which shares photographs and stories from random New York City residents. She turned heads by describing her life as a stripper in 1960s and 1970s New York, calling herself “the only Black girl making white girl money” at the time. Her stripper name, she said, had been Tanqueray, after the brand of gin.

Stanton’s post featuring Tanqueray, whose real name is Stephanie Johnson, went viral. It became the most liked post of all time on the Humans of New York Instagram account, and received coverage in media sources from BuzzFeed to The New York Times. In response, Stanton conducted a series of interviews with Johnson, intending to make a podcast in which she narrated her life story. Unfortunately, Johnson began suffering from health issues and became unable to pay the rent for her apartment. Stanton pivoted, turning the podcast into a fundraiser. Johnson would tell her life story in a series of posts on Stanton’s blog, the first time an entire life story had been shared on Humans of New York. Stanton started a GoFundMe page for Johnson with the initial goal of raising $300,000 for her rent and medical treatment.

Humans of New York stardom was far from the first brush with fame Johnson experienced. Through the 32 posts Stanton made chronicling her life story, Johnson described rubbing shoulders with everyone from rhythm-and-blues legend James Brown to department-store magnate Alfred Bloomingdale. A sex worker friend of hers was allegedly set up with the president of the United States every time he visited New York, though Johnson remains tight-lipped on who the president in question was.

But Johnson’s story is more than just scandal and salaciousness. Her life in New York traces the outlines of the sweeping social changes of the time. She fell in love with a white Italian-American man and married him at a time when interracial marriages were still illegal in many states. The marriage lasted only weeks, and after they had divorced, Johnson got the mobster Joe Dorsey to intimidate her ex-husband into leaving her alone.

The civil rights movement of the 1960s is visible, if not directly addressed, in the experiences Johnson had as the only Black woman in the clubs where she danced. At one point, she was caught in the middle of an argument between Brown and members of The Temptations, two hugely popular Black musical artists at the time, about whether it was okay for Black men to date white women. Having grown up in a mostly white neighborhood in Albany, New York, where she did ballet and learned Latin at the insistence of her abusive, social-climbing mother, Johnson only discovered Black culture once she came to New York City at the same time Black consciousness and Black power were starting to become major movements.

The trajectory of New York City is also brought up in Johnson’s stories. In one of her last posts on Stanton’s blog, Johnson laments how New York has changed since the days when she was Tanqueray. When Johnson’s career was at its peak, New York was in decline. Crime was increasing precipitously, and tens of thousands moved out of the city every year. Since then, New York has turned around. Its population and economy have boomed, and the clubs and adult theaters Johnson frequented around Times Square have been replaced with tourist shops. The city is more expensive than it has ever been, though, and Johnson is nostalgic for the camaraderie provided by the urban dispossessed. She wistfully notes, “Sure, New York is more family friendly now — but not everyone has a family.”

As a downtrodden figure living through decades of American history, serendipitously meeting important figures, it is tempting to compare Johnson to the title character of the classic 1994 film “Forrest Gump.” But this comparison misses the point of both stories. “Forrest Gump” sanitizes the tumult of the 1960s and 1970s. While the fictional Gump, an oblivious white Southerner, witnesses and influences historical events, historical events do not influence him. Johnson paints a sadder but far more complete picture of America. Her life recounts some of the most chaotic times in American history, warts and all.

When Johnson was 18 years old, she had her palms read by an elderly inmate of a women’s prison. She was told she would live all her life in New York City. She would have a tough and lonely life, but one day, she would become famous. All these years later, Johnson claims that everything the woman predicted came true.

“Well, almost everything,” she said in one of her blog posts. “(The fortune-teller) told me that I’d come into some real big money one day. And that better happen quick. ‘Cause I’m already 76.”

By the time Johnson finished telling her story, the GoFundMe established in her name had raised over $2.6 million. “Tattletales from Tanqueray,” Johnson’s life story, can be read in full at www.humansofnewyork.com or on Instagram at @humansofnewyork.

Subscribe to the Mossy Log Newsletter

Stay up to date with the goings-on at Lewis & Clark! Get the top stories or your favorite section delivered to your inbox whenever we release a new issue.

Leave a Reply