By Leslie Muir /// Opinions Editor

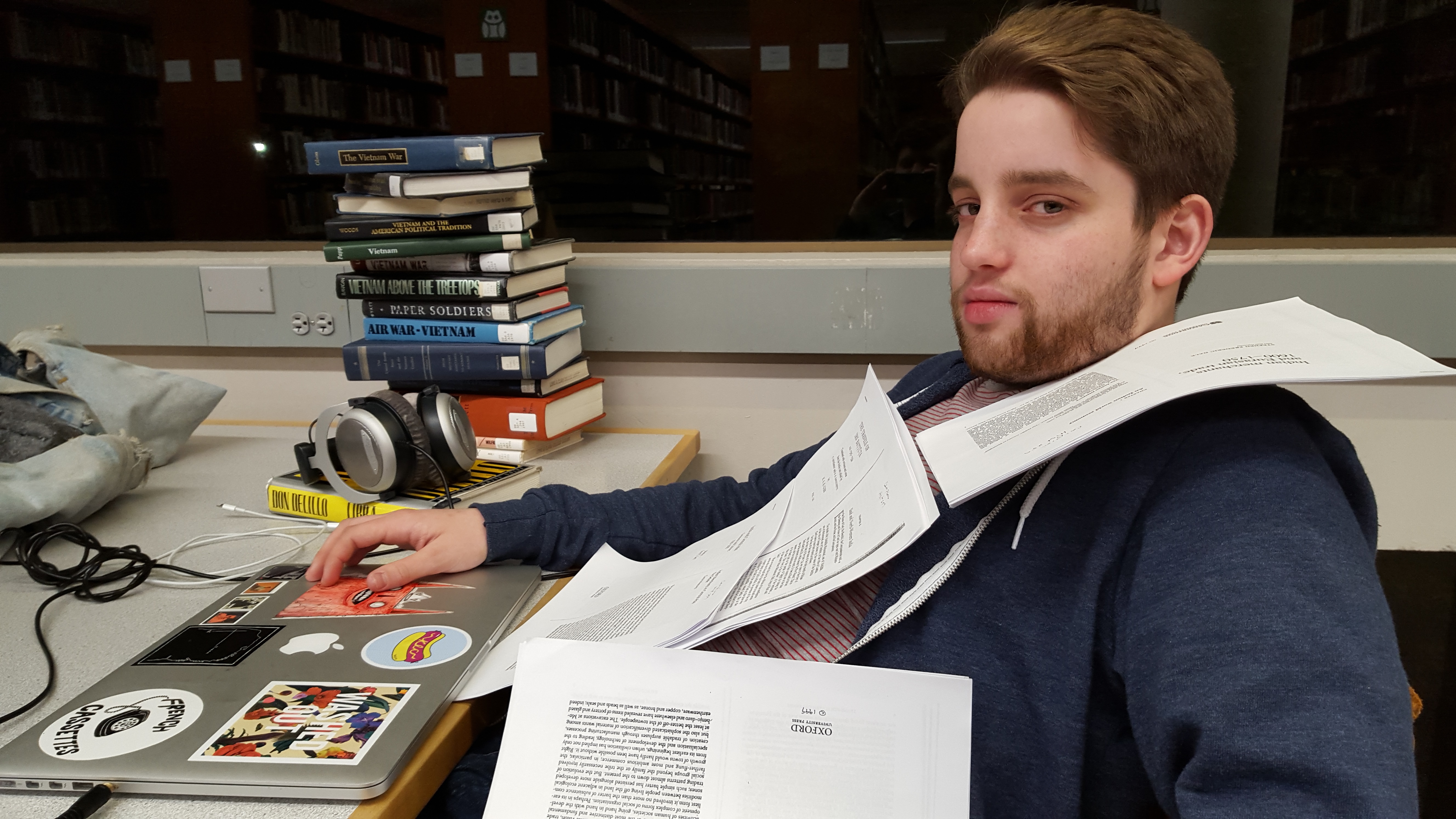

You can always find a Historical Materials student at their designated library table.

Historical Materials, or Hist Mat, is the only class on the undergrad campus with a table in Watzek Library specifically dedicated to its students. They need that reserved space. This rigorous class asks a lot of its students, who are all History and Art History Majors and minors.

Approaching the Historical Materials table on a Sunday afternoon, one finds Hannah Exeler ‘18, Erin Schimmel ‘18 and Kaia Mann ‘18, as well as a handful of others, hunched over piles of books. They do not look up from their computer screens as they answer questions about their day, the first being how long they have already been there.

“About 3 hours,” Exeler said right away. “I’m in here about 15 hours a week.”

Another history major, Mann, quickly chimes in.

“I’m in here 15 to 20 per week. I do all of my work in the library, because you can’t take some of the books out,” Mann says.

Jokingly, Schimmel stands up to make a comment.

“Could you ask people not to sit here if they aren’t in the class or aren’t history students?” Schimmel laughs. Even jokingly, this table is reserved for Hist Mat students for a reason. The entire group was upset earlier that day at the discovery of a Twilight book that was on their Hist Mat book cart. Other students not taking their space seriously is seen as disrespecting the intense and rigorous work that they accomplish throughout the term.

The Hist Mat table and the reference books are intrinsically linked through professor assignments and location. This means that many Hist Mat students are forced to stay inside of the library for many hours a week whether they like it or not.

These students are pushed to the limits of their academic abilities as they embark on a project that is considered to be considered a premature thesis. On the very first day of class they are told to begin working on their final: a 20 page historical artifact that they are asked to add 100 plus annotations to. The final project resembles a book, with a table of contents, acknowledgments page, historical methods prelude and annotations throughout.

In addition to this project, students are given regular weekly and monthly assignments to exercise their use of different forms of historical materials. Students select their own subject for the culminating materials project. The only requirement is that the work has never been touched by the academic light. This means that students are working with texts that have never been annotated or studied before, such as personal family letters, diary entries and unpublished letters from various figures they have researched.

The ability to annotate work is heavily drilled in through weekly lists of assigned annotations that end up turning into something of an academic showdown, with history majors assigning each other questions from professor-assigned texts. These students try to stump one another with questions about historical texts that their classmates then track down in Watzek and correctly cite in their answer.

Other longer assignments include preparing for and conducting an oral history interview with a Lewis & Clark alumni that is added to the school’s archives for the History Department’s Oral History Project. Students research deceased Portland residents using nothing but a gravestone as a jumping off point, and read copious amounts of papers and articles that all highlight a different skillset of a successful historian. This is history bootcamp. Like with any battle, it is important to enter it with others at your side.

“I like having a table and the comradery,” Exeler said. This class is seen as a right of passage amongst history students, and introduces them to many of the same students in their graduating year.

Exeler added that it would have been comical if their professor for the Spring ‘16 term, Andy Bernstein, had included the Stephanie Meyer book to annotate.

When asked how many books they had handled all three have to think about their answer for a minute.

“Probably 12, just today,” Exeler said.

“Like, 50 or 60 total,” Schimmel tentatively added.

Between the ten to twelve different annotations that students are asked to complete every week, as well as the other research they are asked to accomplish, this may be an understatement.

“You always feel like you’re falling behind even when you’re constantly doing work,” Mann said. The work that Hist Mat students do in just one term is incredible in its volume and depth. Although the class is not available or recommended to the general population of liberal arts students, History majors see it as an important and beneficial moment in their education, despite the long hours and workload.

“Everyone’s kind of dying, but we’re all doing it together,” Exeler said. The other students around her nod in agreement, without looking up from their computer screens for even a moment.

Subscribe to the Mossy Log Newsletter

Stay up to date with the goings-on at Lewis & Clark! Get the top stories or your favorite section delivered to your inbox whenever we release a new issue.

Leave a Reply