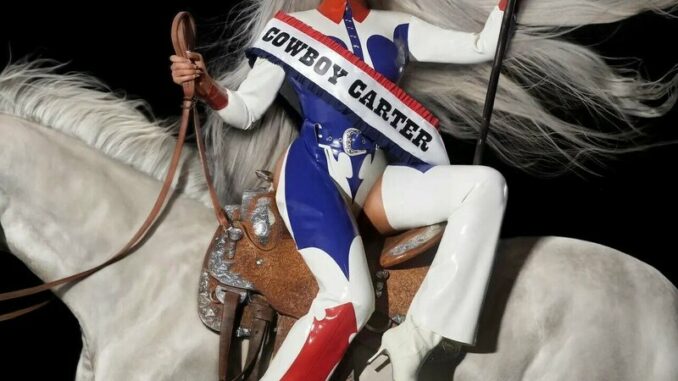

Unless you have been living under a rock these past few weeks, you are probably aware that Beyoncé has dropped her eighth studio album, “Cowboy Carter.” In anticipation of the album, Beyoncé released two singles, “Texas Hold ‘Em” and “16 Carriages” on Feb. 16, about a month prior to the release of the full album on March 29.

The album has unsurprisingly broken streaming records and reached the top of the all-genres Billboard 200. Notably, the album shattered the country glass ceiling when Beyoncé became the first Black woman to top the country Billboard.

“Renaissance,” Beyoncé’s previous album, a flamboyant dedication to house and hip-hop, was the first act of an ongoing project. References to act II are incorporated heavily into “Cowboy Carter.” At first glance of the track names, you might be wondering if spellcheck was omitted during the editing process, but the doubling of “i”s, like in “Ameriican Requiem,” or “Blackbiird” is certainly an intentional nod to the artist’s second installment of a greater undertaking.

The album is a triumph for Beyoncé as an artist and entrepreneur, but it is also clear that these 27 tracks were created to bring an entire history and community to the forefront of

popular culture.

Country music strikes a sensitive chord with many Americans because it is highly entwined with American identity, or rather, white American identity. One of the most pernicious myths born from American racism is the erasure of African American contributions to Southern culture. Nearly every facet of Southern tradition — food, fashion, language

and, of course, music — has been shaped by the unique experiences of Black Americans of past and present. “Cowboy Carter” is a love letter to Black Americans in the South, as well as a reclamation and exploration of the genre of country and its history.

The beginning song, “Ameriican Requiem,” is a gospel anthem framed by a background choir and synth organ that echo throughout the album. The last track “Amen” concludes with the lines “We’ll say a prayer for what has been / We’ll be the one who purify our father’s sins / American Requiem / Them old ideas are buried

here / Amen.”

There is a lot to unpack in just these few lines, but in essence, Beyoncé is calling on her American listeners to unpack the complexity, darkness and beauty in our country’s history. In genre, style and subject matter, Beyoncé pays homage to the foundations of American music, which has been falsely attributed solely to white artists.

“Smoke Hour Willie Nelson” is a spoken word interlude featuring the voice of quintessential country star Willie Nelson, weaving in background static emulating an old-time radio playing classic songs that take listeners back in time. Musicians Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Chuck Berry and Son House are featured on this track, each prominent to foundations of rock, R&B and country.

Son House was an influential Delta blues guitarist and singer during the early 20th century. Chuck Berry is famously known as the “godfather of rock ’n’ roll” and captured his audience by dancing across the stage with electric guitar in tow. But, even before Chuck Berry, there was Sister Rosetta Tharpe, rock’s “godmother” who brought the lyrical themes and cadences of gospel music into the mainstream. Without her masterful electric guitar playing, and powerful voice (often harmonizing with vocalist Gladys Knight), there would be no Elvis Presley, Beatles or Rolling Stones.

These three artists demonstrate the profound changes in Black American music over just a few mere decades. Son House represents the era of bluesmen, or “songsters,” many of whom were preachers or strongly rooted in the church, accompanied by their own fingerpicking bass and melody. Rosetta Tharpe ushered in the age of electric guitars, shifting away from acoustic resonators, as well as increasing the visibility of African American musical tradition nationally. Instead of exclusively performing in local Southern venues, Tharpe and Berry broke out onto large stages worldwide. The musical transformations through the mid-20th century were no doubt a product of adapting technologies and U.S. racial attitudes.

Moving forward in the album on another radio interlude, “The Linda Martell Show” honors the first Black woman to perform at the Grand Ole Opry, with Martell introducing the next track on the album “Ya Ya.” Martell is considered to be the first Black female country star, breaking onto the scene in 1970 and appeared on popular radio and television broadcasting and performing with artists like Waylon Jennings and Hank Snow. Martell faced criticism and harassment from white audiences and struggled to achieve the same success her white male counterparts in the country music industry did.

Another tie to Black history in the album is “Blackbiird,” a cover of The Beatles’ hit song. The Beatles were neither American nor country musicians, but, as established earlier, early African American music was the base of rock ’n’ roll. The original song features themes of rising up in the face of darkness, and Paul McCartney has recently expressed that the song was heavily inspired by the

African-American fight during the Civil Rights Movement. For this cover to be sung by Black women, several decades after its original release, is a powerful statement. In addition to Beyoncé’s voice, Tanner Adell, Tiera Kennedy, Reyna Roberts and Brittney Spencer sing on the song, all up-and-coming Black women in country music.

“Texas Hold ’Em,” one of the two preview singles of the album, also weaves in Black past and present with a banjo introduction, played by the multi-instrumentalist and arguably the most accomplished folk-revivalist of our generation, Rhiannon Giddens. Giddens has founded several musical groups such as the Carolina Chocolate Drops and Our Native Daughters, and has toured with Yo Yo Ma’s Silk

Road ensemble.

Giddens has been a leading voice in the reclamation of the banjo as a Black instrument. The banjo is often tied to an old-fashioned, white, country narrative, so many would be surprised to learn that the banjo is an African instrument in origin. Enslaved Africans brought the gourd-based, percussive, stringed instrument from their homeland to America and used its music to preserve the culture that was stripped from them.

Over time, like many other contributions by African Americans, the processes of co-opting and

cultural diffusion buried the true origins of the banjo. Giddens wrote a foreword in the recent book “Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History” by Kristina R. Gaddy that delves deeply into the topic.

Most “Cowboy Carter” tracks do not fit into the country genre in the most literal sense. They pull heavily from pop, R&B and gospel, even incorporating classical Italian opera in “Daughter.” But the question of genre is a central theme throughout, asked explicitly through lyrics and answered implicitly with the music. In no track is this more clear than “Spaghettii” which begins with the spoken voice of

Linda Martell.

“Genres are a funny little concept, aren’t they? Yes, they are / In theory, they have a simple definition that’s easy to understand / But in practice, well, some may feel confined,”

Martell says.

The rest of the song is traditional hip-hop, switching halfway through to a more country feel with vocals

from Shaboozey.

I genuinely enjoyed every song on this album, and maybe that is because I am a die-hard Beyoncé fan, or I just have an appreciation for

genre-bending. You might not love every song, but the beauty of the vastness is that there is something everyone can appreciate. Despite the powerful messages throughout the album, there is so much joy and humility in each track. There are tender and personal moments, like “Protector” and “II Most Wanted;” there are silly and celebratory moments like “Ya Ya” and “Riiverdance;” and there are many moments that are deeply spiritual, connecting with those who came before her.

The reclamation of country is not a new concept, even for Beyoncé herself. Lemonade called on her Texas and Louisiana roots with the song “Daddy Lessons” establishing her ability to thrive in the genre. Despite success, when she performed the song alongside The Chicks’ at the 2016 Country Music Awards (CMA’s), Beyoncé was met with racially-charged backlash.

KNTRY might be the most apt descriptor of “Cowboy Carter”, or in the queen’s words herself: “This ain’t a country album. This is a ‘Beyoncé’ album,” posted on her social media. Blackness is at front in center, but Beyoncé pays respect to country legends of all backgrounds. The 27 tracks may not all sound “country” in the traditional sense, but it is apparent that this album was made to subvert rather than emulate what is to be expected of the genre.

Subscribe to the Mossy Log Newsletter

Stay up to date with the goings-on at Lewis & Clark! Get the top stories or your favorite section delivered to your inbox whenever we release a new issue.

Leave a Reply