Raise your ethically sourced chai latte (with oat milk, of course) in celebration folks, Portland has claimed the title of “Most Hipster City” in the United States.

The ranking comes from MoveHub, a service that analyzes the costs and benefits of various international shipping companies that help people move abroad. Their 2020 survey combined five data points, including “the number of vegan eateries, coffee shops, tattoo studios, vintage boutiques and record stores per 100,000 city residents,” according to their website. Each city then earns a Hipster Index score out of 10. In the latest version of the survey, MoveHub analyzed 446 cities across 20 different countries.

But what qualifies something as a “hipster”? According to Merriam-Webster, a “hipster” is one who is “unusually aware of and interested in new and unconventional patterns.” This usage dates back to 1940, primarily referring to the realms of jazz and fashion. An additional use of the label “hipster” refers to prohibition when people would carry hip flasks.

In modern times, “hipster” is a blanket statement used to refer to someone who follows trends closely, particularly those that fall outside of the cultural mainstream. MoveHub suggests that this characterization applies primarily to 20 to 30-year-olds who align themselves with various subcultures.

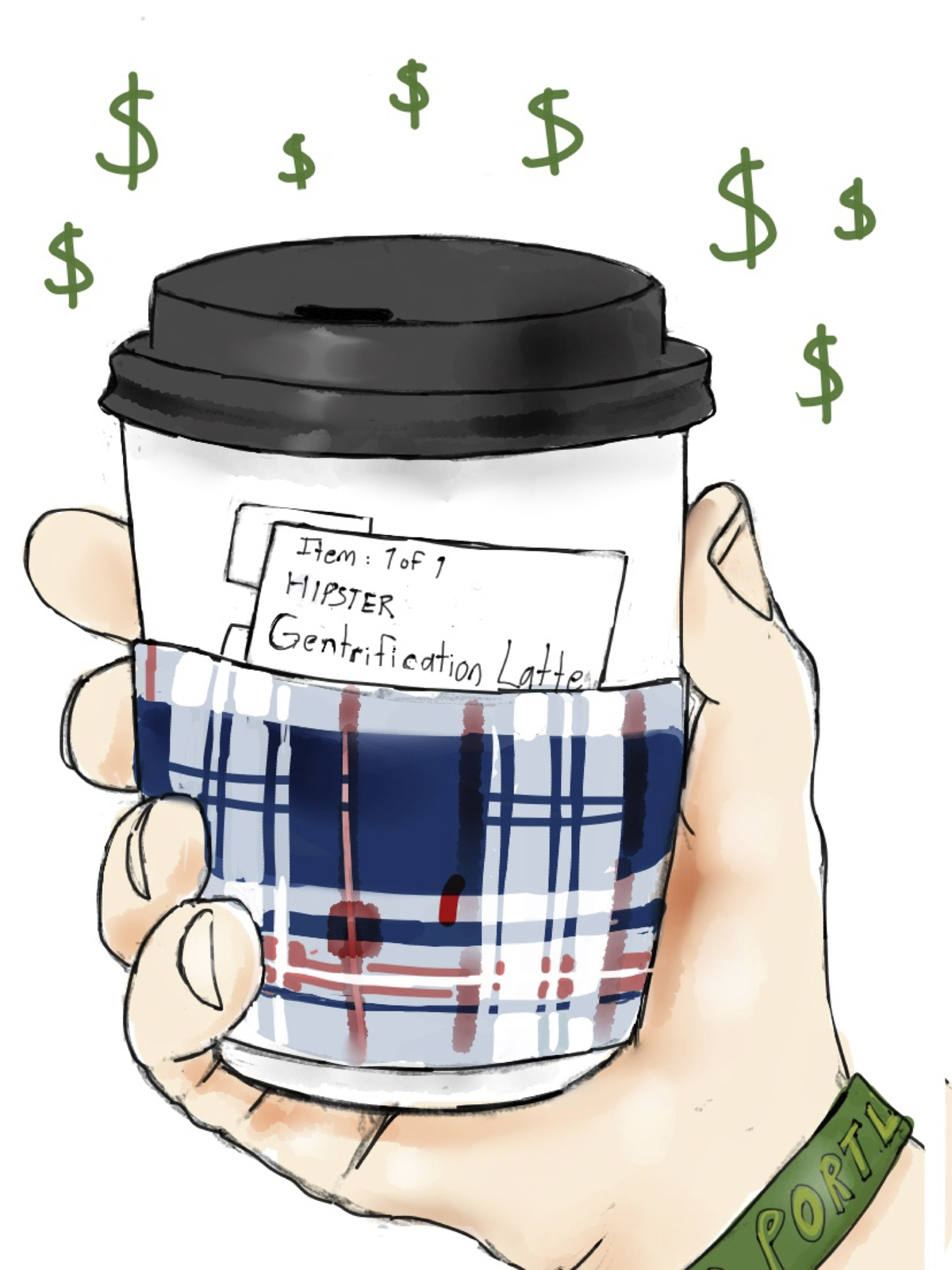

Despite the joyful living and free-spirited existence that hipsterdom encourages, it can come at a high cost to more underprivileged residents of urban areas. Gentrification is rampant in many, if not all, of the cities identified by MoveHub’s index.

Independent news organization The Conversation published an article in 2018 by researcher Melissa Tandiwe Myambo that explored the argument of whether hipsters could be classified as modern-day “colonizers.” Myambo illustrates that despite the many areas of social change hipsters advocate for, they are often caught in the center of a paradox.

“They appear progressive, but they actually demonstrate some parallels with the practices and ideologies of the settler-colonialism of earlier centuries,” Myambo writes.

Myambo tracked the movement of hipsters relocating to lower-income, urban neighborhoods and the real estate developers that followed as a result of the influx. According to Myambo, hipsters and colonizers alike “displace less powerful occupants.”

Problematically, the narrative of this displacement is often curtailed around promises of “urban renewal” or “regeneration.” However, Myambo demonstrates how these false narratives allow for the displacement of social responsibility as well. Without accountability, Myambo warns that gentrification combined with the “hipster’s nostalgia” for past eras can lead to deeper traces of xenophobia and racism. A consumeristic demand for alternative milk and flannel shirts suddenly is not as harmless as it once seemed.

Despite contributing to gentrification, Myambo points out that hipsters also create communities based on eco-activism, queer rights, women’s rights and many other noble causes that strive to create a more equitable world.

As many of us were drawn to Portland for its reputation of acceptance and quirky celebration of individualism, it is important to remember the long-term impacts it has on other communities that deserve the same share of space in the city we call home.

Subscribe to the Mossy Log Newsletter

Stay up to date with the goings-on at Lewis & Clark! Get the top stories or your favorite section delivered to your inbox whenever we release a new issue.

Leave a Reply