What do Grimes, Trisha Paytas, Nyan Cat and Leonardo da Vinci have in common? Absolutely nothing, or at least that is what I thought. The answer is actually non-fungible tokens (NFTs).

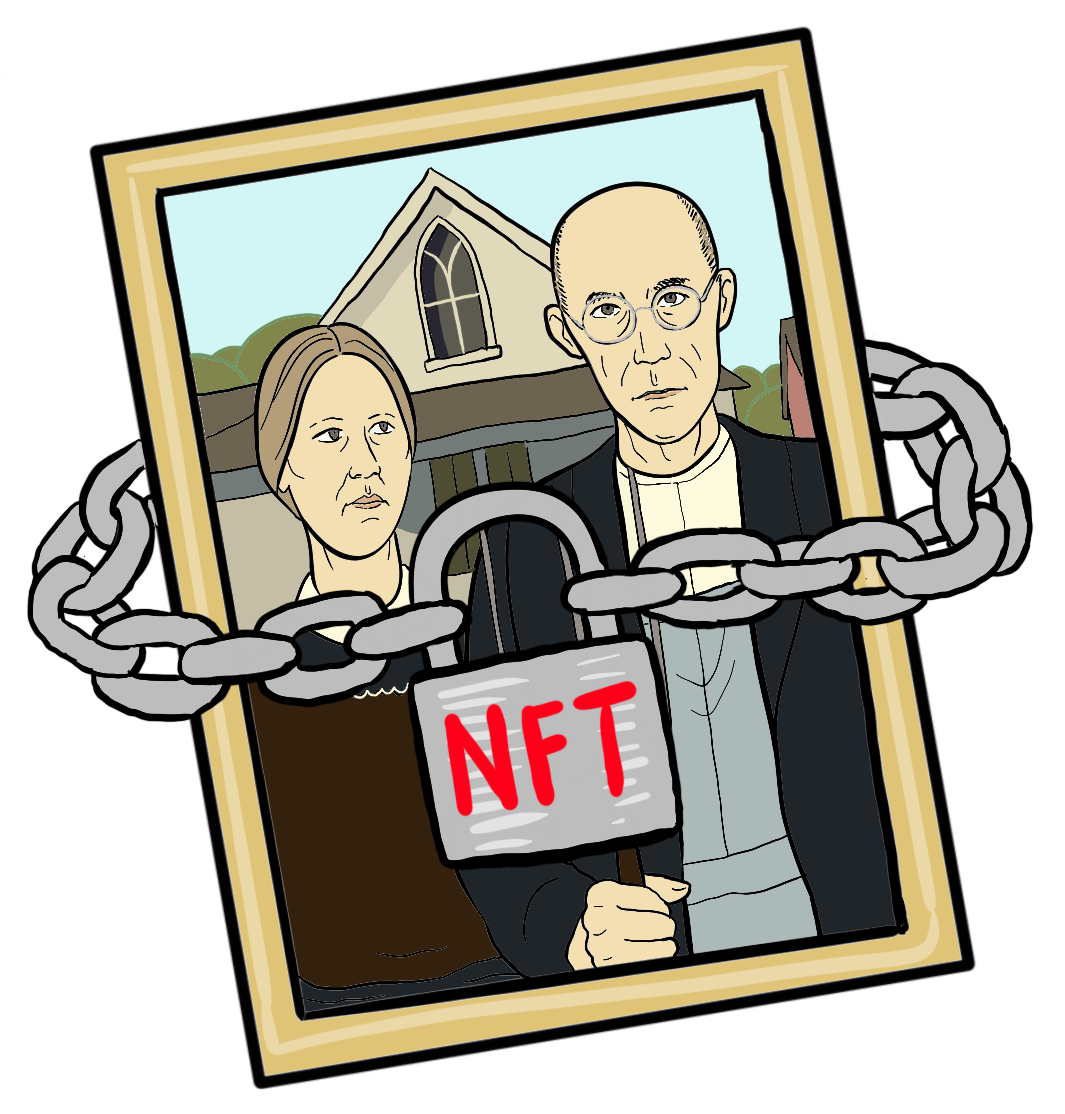

Several sources encourage people to think about NFTs as one-of-a-kind trading cards of sorts. According to your general Wikipedia search, “A non-fungible token is a unit of data stored on a digital ledger, called a blockchain, that certifies a digital asset to be unique and therefore not interchangeable.”

The most important thing to understand is that NFTs are certifiers of a digital asset’s uniqueness — a digital asset can be anything ranging from an artwork, a song, a video or even a meme. For example, say an artist sold a digital painting as an NFT. The person who buys it owns the original through the NFT’s certification. Contrastingly, the person who takes a screenshot of the painting, and makes it their screensaver, just has a copy. The latter scenario would be the equivalent of going to the Louvre Museum and buying a postcard of the “Mona Lisa,” or at least that is the idea.

The sheer range of what people are selling as NFTs is absurd. Collaborating with her brother Mac Boucher, Grimes has sold several digital artworks accompanied by her music as NFTs, calling it the “War Nymph” collection. True to her emblematic ethereal style, these works combine fantasy and science fiction, featuring graceful images like sword-wielding cherubs flying in space. In contrast, viral YouTube and TikTok star Trisha Paytas is selling a photo of herself with makeup running down her face titled “trisha paytas goes to the mental hospital” on the NFT platform OpenSea. Moreover, Jack Dorsey, the CEO and co-founder of Twitter, recently sold his first tweet as an NFT.

NFTs have been a point of contention with a lot of the discussion revolving around their impact on the art world. However, the art world has already accommodated their emergence.

The art market, for example, has seen remarkable profits from the sale of NFTs. Sotheby’s and Christie’s, two of the world’s biggest auction houses, have already sold many millions of dollars worth of them. On March 11, Christie’s sold $63.9 million of digital art by Beeple (aka Mike Winkelmann). Grimes’ “War Nymph” collection sold for around $6 million on Nifty Gateway and Dorsey’s first tweet sold for $2.9 million on a platform named Valuables by Cent.

Although the high price points of these examples might make NFTs seem inaccessible to the general public, they have actually opened up a new system for collecting digital art — a system that empowers anyone, from anywhere, to collect verifiable, original works of digital art. Assistant Professor of Art and Studio Head of Digital Media at Lewis & Clark, Brian House described the sales dynamics of NFTs as more “distributed,” “online” and “fast-moving.”

“Anyone can get in on it,” House said. “All you need is a computer, and you can start collecting NFTs and trading NFTs, and whatever else. So it’s a method that opens the art market up to a lot of new ways of participation from a lot of people, and also allows people to directly invest in artists and their work.”

In addition to creating space for new art collectors, House also said that NFTs benefit digital artists who are popular on social media platforms but may not be recognized by the mainstream art world, giving them a way to monetize their craft.

“Up until now, the ability to monetize sharing that content (on the Internet) has not really been there,” House said. “So Facebook, Instagram … Twitter, whatever else, the platforms profit, but not necessarily the people … So in coming up with a mechanism to monetize that, you know, that can be a benefit to the creators.”

However, House does not believe this is always a good thing. For one, he thinks it might reduce the friction between unconventional and traditional art communities. Before, many digital artists thrived solely on social media platforms. In other words, they operated outside of or separate from the mainstream art world (think of museums, galleries, auction houses, etc.). But with the rise of NFTs, the traditional art world has seen that digital art can be profitable and they have latched onto it, selling it at high margins. For House, this means capitalist logic has taken control of digital art.

“I would like to think that there is something that art holds that is not purely created for a commodity,” he said.

House also thinks digital artists are now more likely to be evaluated through a “metric” lens, where things like how many followers they have on social media determine their value.

“There’s nothing subversive about this,” he said. “Maybe that’s the quote. I want art to be subversive to some extent, and to comment and to challenge the society that we live in. And there’s nothing subversive about NFTs. Like Logan Paul selling Pokemon cards is not subversive. So I don’t know about playing into that market.”

Another problem with NFTs, for House and many critics and artists alike, is their substantial environmental impact. Similar to cryptocurrency, every time an NFT is created or “minted,” it begins a process called mining, which consumes a lot of electricity.

“To successfully add an asset to the blockchain’s master ledger, miners must compete to solve a cryptographic puzzle, their computers rapidly generating numbers in a frenzied race of trial and error,” an article from The New York Times said. “As of mid-April, miners were making more than 170 quintillion attempts a second to produce new blocks, according to the trading platform Blockchain.com. (A quintillion is 1 followed by 18 zeros.) The miner who arrives at the right answer first is the winner and gets her or his asset added to the blockchain.”

Some miners have entire warehouses filled with computers devoted to this process.

Ethereum, the most popular blockchain platform for NFTs, has particularly been criticized for how much energy its current “proof of work” model (as described in the quote from The New York Times) consumes.

According to Time Magazine, “Ethereum mining consumes about 26.5 terawatt-hours of electricity a year, nearly as much as the entire country of Ireland and its almost 5 million residents.”

Due to the environmental footprint of minting NFTs, many artists such as Chris Precht have renounced making them. Other artists have continued to work with them given how lucrative they are, citing that large corporations should be criticized for climate change rather than individual artists.

“I’ve been so disappointed by how quickly they’ve jumped on this bandwagon of NFTs,” House said. “And it could be because art is a precarious industry. These people need to make a living in some way, and if this is a way to help them, I can see that logic. But, it’s sad because it just shows the reach of kind of neoliberal logic and that the short-term gain from selling work in NFTs ends up having a higher value than the habitability of this planet for humans.”

Ethereum is currently working on a “proof of stake” model that would consume less energy, where instead of competing against each other to solve cryptographic puzzles, miners would be rewarded for how much cryptocurrency they already own. There are also other platforms that do not require the same computational power as Ethereum.

It is unknown if NFTs will persist through their social and environmental controversies, but House thinks they are more than a fad.

“I think it’s something different than just like a trend, or something that’s in fashion that gets hyped,” House said. “I think there is something a little more volatile behind it and that has a little bit more of an effect. Something like NFTs is going to be around, just like the Internet is not going away anytime soon. Digital production is not going away. But it can change very quickly.”

In relation to the LC art department, House has been considering incorporating NFTs into his class curricula, using one of the more sustainable platforms.

“Art has to be about the contemporary discourse,” he said. “And if this is what’s going on, then yeah, I think Lewis & Clark students will debate it and participate and figure out their own take on it.”

Subscribe to the Mossy Log Newsletter

Stay up to date with the goings-on at Lewis & Clark! Get the top stories or your favorite section delivered to your inbox whenever we release a new issue.

Leave a Reply