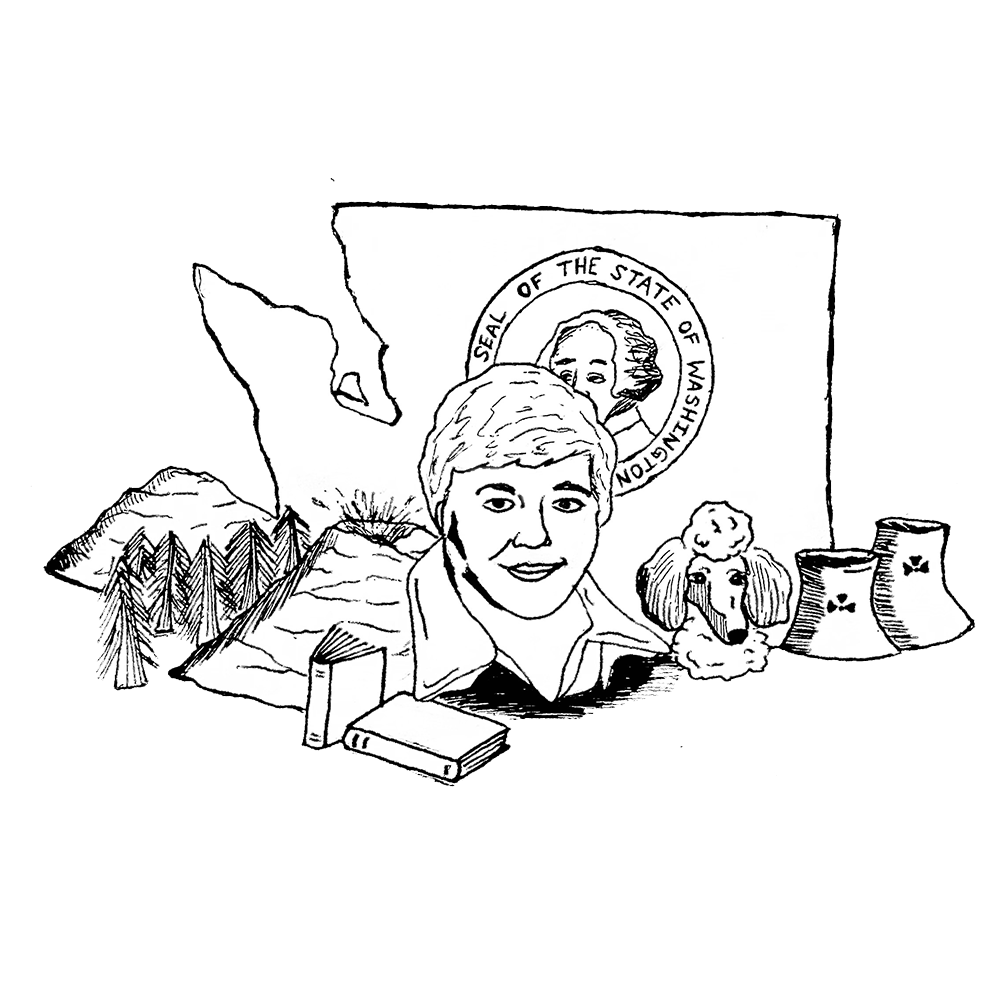

Dixy Lee Ray reveled in contradictions. She had an infamous temper and ego, yet she was fiercely intellectual. She lived on a farm on a small Puget Sound island in the last decades of her life, though she was also pro-nuclear power. She was a high-ranking political leader, but her political beliefs belonged to neither party. She was a female scientist and politician at a time when women in either role were vanishingly rare.

Ray served as governor of Washington state from 1977 to 1981 at the height of a long career spent connecting science and politics. Born Marguerite Ray in Tacoma, Washington, in 1914, Ray was energetic and driven from a young age: At age 12, she became the youngest girl ever to climb Mount Rainier. Her parents called her “little dickens,” an expression meaning mischievous child. As a teenager, Ray adopted an abbreviation of this nickname, Dixy, as her legal name, believing her birth name to be “too feminine.”

Ray graduated from Mills College as valedictorian, and by the mid-1950s she was a professor of marine biology at the University of Washington. One of the university’s only female scientists, she turned heads for more than her gender. She would arrive to work in a sports car, with one of her many dogs riding shotgun. She wore athletic clothes to formal events. She lived in a hostel-like boarding house above a restaurant — which was probably how she could afford a sports car on a professor’s salary.

In 1964, Ray served as chief scientist on a research ship in the Indian Ocean, aboard which, according to her niece Carolyn Strong, she participated in a mutiny because she believed the crew’s scientific work was inefficient.

“She took control and locked the captain in his quarters, as I understand, and got the staff to work together,” Strong said.

After leading a mutiny on the high seas, Ray returned to Seattle and created the first hands-on science museum. She had co-founded the Pacific Science Center in 1962 as part of her lifetime goal to improve the average person’s understanding of science. Disappointed by the museum’s static, “hands-off” exhibits, she took control of the museum and replaced the exhibits with interactive displays of scientific principles. She promoted the revamped Pacific Science Center by hosting a popular science show for children on Seattle’s KCTS-TV — the network that would later create “Bill Nye the Science Guy.”

In 1973, in a ham-handed attempt at increasing his cabinet’s diversity, President Richard Nixon requested a female scientist to chair the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), which regulated and designed nuclear power plants. Washington Sen. Warren Magnuson recommended Ray, and she was appointed. Before taking office, Ray drove a mobile home across the United States to Washington, D.C., stopping along the way at every nuclear power plant and research station in the country to ask the staff about the changes in leadership they wanted to see at the AEC.

Upon arriving in D.C., Ray found that the government wanted her role to be effectively ceremonial. Not discouraged, Ray proceeded to run the AEC with an iron fist. Many of the longest-tenured AEC members were fired under Ray’s leadership, and she advocated the reorganization of the AEC on the grounds that no organization can be trusted to regulate the same thing it produces. On her advice, Congress passed the Energy Reorganization Act of 1974, dividing the AEC into two agencies. Ray’s role shifted to the State Department, where she was in charge of appointing scientific attachés to U.S. embassies, among other science-related duties.

Even then, Ray refused to stay in her lane. According to Strong, through her job at the State Department, Ray befriended nuclear scientists from all over the world and eventually worked out a nuclear disarmament plan between scientists in the United States, France, Germany and the Soviet Union. Scientists were not supposed to be working on anything without the knowledge of their superiors, and when Secretary of State Henry Kissinger got wind of Ray’s machinations, she quit in frustration. The plan was never implemented, and Ray drove back to Seattle in her mobile home, where she and her dogs had been living for her entire span of federal service.

Ray proceeded to get involved in her home state’s politics. Inspired by her trek across the nation visiting power plant workers, she crisscrossed Washington, asking people in every county what they wanted from the government. In Washington’s 1976 gubernatorial election, she pulled off a surprise win, despite massive opposition from the state’s political class, and prognostications that no state was ready to elect an unmarried, trailer-dwelling female scientist to its highest office. She was only the second woman in American history to be elected as a governor without having relatives in politics. Though she balanced the state’s budget and increased education funding, her eccentricity and sharp tongue made her deeply unpopular with voters, and she was defeated in the Democratic primary when she ran for re-election. In 1991, she described her single term as governor as “moments of exhilaration, hours of sheer boredom, and seconds of absolute … I think that word shouldn’t be used on air.”

Ray’s most famous political accomplishment surrounded the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens. Long before the public was aware of the volcano’s dangers, Ray had been in contact with scientists who warned that an eruption was imminent. She examined the situation firsthand, circling the mountain in the governor’s private plane. On April 30, 1980, she declared a “red zone” surrounding Mount St. Helens in which all people were excluded. When the mountain blew on May 18, the Forest Service estimated her restrictions saved up to 30,000 lives, but the praise Ray received was not enough to win her re-election.

Ray was not done reinventing herself. After politics, she became an acclaimed artist. Strong says she took up wood carving to release stress during her term as governor, inspired by the totem poles carved by members of the Kwakiutl Nation that stood outside the Pacific Science Center. She received numerous commissions for large pieces of art, including a carving in the Weyerhaeuser forestry company headquarters. Ray became so recognized for her carvings, the Kwakiutl named her an honorary tribal member, conferring on her the title of “Umah,” or “respected lady”.

Strong’s anecdotes of Ray paint a picture of a woman who was profoundly eccentric, but friendly and altruistic. When Strong was in college, Ray offered to lodge her for the summers at her farm on Fox Island in Puget Sound, where Ray’s mobile home had been permanently parked. There, Strong says, Ray would cook international meals for her, and they would discuss religion and philosophy late into the night.

As governor, though, Ray’s temper was central to her reputation. After hundreds of employees of the previous governor protested being fired, she taunted them, offering to send them Kleenex boxes. In response to constant negative media coverage, Ray named pigs at her Fox Island farm after reporters in her press corps, then made the pigs into sausages and offered them to the very same reporters.

Ray even divided her fellow scientists. Though physicist Edmund Teller attempted to recruit her to run for president in 1980, at her death in 1994 several conservationists went as far as to label her “unscientific,” largely due to a pair of books she had written in her last years in which she appeared to cast doubt on climate change. Most who knew Ray, including Strong, argue this is a misunderstanding.

“She said, ‘We don’t have to go back to the 1600s to solve environmental problems,’” Strong said.

Science historian Erik Ellis agrees, saying in a 2006 essay on Ray that she was not denying climate change, but trying to increase public understanding of it, as people associated living environmentally with a lower standard of living. Her strong faith in the power of science to solve problems, Ellis says, was unfashionable in the pessimistic ’90s.

Ray never married, wore her hair short and had hobbies some might have perceived as masculine at the time. Her sexual orientation will probably remain lost to history, but Ellis argues that her “tomboy” identity was essential to her success in the male-dominated fields of science and politics. As a masculine woman, men saw her not as a sex object, but as one of them.

Perhaps the best way of understanding Ray is as a woman jarringly ahead of her time. Long before today’s partisan polarization, she advocated for the abolition of political parties — Ray claimed she ran for governor on the Democratic ticket because the Republican primary was already too crowded, caring little about her official party affiliation. She recognized that nuclear power was safe at a time when the environmental movement was vehemently against it. The greatest irony of Ray’s life is that, despite her perceived opposition to environmentalism, if more people had listened to her on nuclear power, climate change would be less of an issue today.

To this day, even as women have made gains in politics, America has yet to produce another female politician with Ray’s willingness to take a blowtorch to political and social norms. And as rare as it was to be a woman in politics at the time, it was, and still is, rarer to be a scientist in politics. As we face compounding global crises, maybe what we need is another Dixy Lee Ray — a pragmatist who recognizes that truth does not belong to a political party.

Subscribe to the Mossy Log Newsletter

Stay up to date with the goings-on at Lewis & Clark! Get the top stories or your favorite section delivered to your inbox whenever we release a new issue.

Great article on Dixie Lee Ray. Fascinating, seemly without biases, presenting a wealth of interesting information on her life. I worked at Hanford in 1977, a newly graduated engineer from Illinois. She and the beautiful PNW inspired me.

Love getting your youthful views in the last several paragraphs. Makes me realize that over time issues get sorted out….the emotional solutions are dulled and the common sense more practical solutions are reconsidered. Thanks for your fine work!

Mr. Parsons, You are young, were, obviously not alive when Dixie Lee Ray was leading the Atomic Energy Commission, then Governor. I would read newspaper articles about her.

Despite your youth, no one has written more perceptively, fairly, or intelligently about Dr.-Governor Dixie Lee Ray. You have such deep attunement to people, human issues, time periods. Reading your wonderful article, I received more of her totality then ever I did, reading about her, or even, listening to her interviews. Thank-you!