Herbert Bayer, one of the most influential students and teachers of an early 20th century art school called the Staatliches Bauhaus, once said, “we write everything in lowercase because it saves time. why two alphabets, when just one achieves the same thing? why write in capitals when we can’t speak in capitals?” This quote demonstrates the subversive attitude towards convention central to the Bauhaus philosophy.

Posters featuring the iconic Bauhaus all-lowercase font can be found in the Watzek Library atrium as part of the new Special Collections exhibit: The Bauhaus at 100. This exhibit features models of the modernist and innovative designs created at the Bauhaus, along with facsimiles of its founder’s manifesto and publications and photographs of the students and masters at this utopian art school and community in Weimar, Germany.

The Bauhaus was founded by German architect and war veteran, Walter Gropius, who created the Bauhaus in an attempt to mitigate the trauma and misery which saturated German life after World War I. His goal was to create an ideal community where members could learn to regain control over building technology with the support of a tight-knit artistic community.

“I’m really interested in Gropius because he had such an interesting life and was in many ways a demagogue,” German studies major Jack Hanning ’21 said. “He had a unique ability to unite people and guide them but not order them.”

Associate Professor of German Studies and German Section Head Therese Augst worked with German studies students Hanning and Scott Stewart-Rowden ’20 and Head of Special Collections Hannah Crummé this summer to curate the exhibit. The exhibit features Augst’s research on the intrepid weavers of the Bauhaus and Anni and Josef Albers, Hanning’s research on Walter Gropius, and other individuals and particular workshops of the Bauhaus and Stewart-Rowden’s research on the overall history of the Bauhaus. The four searched through the Bauhaus archives to acquire photographs, artifacts and replicas that make up the exhibit.

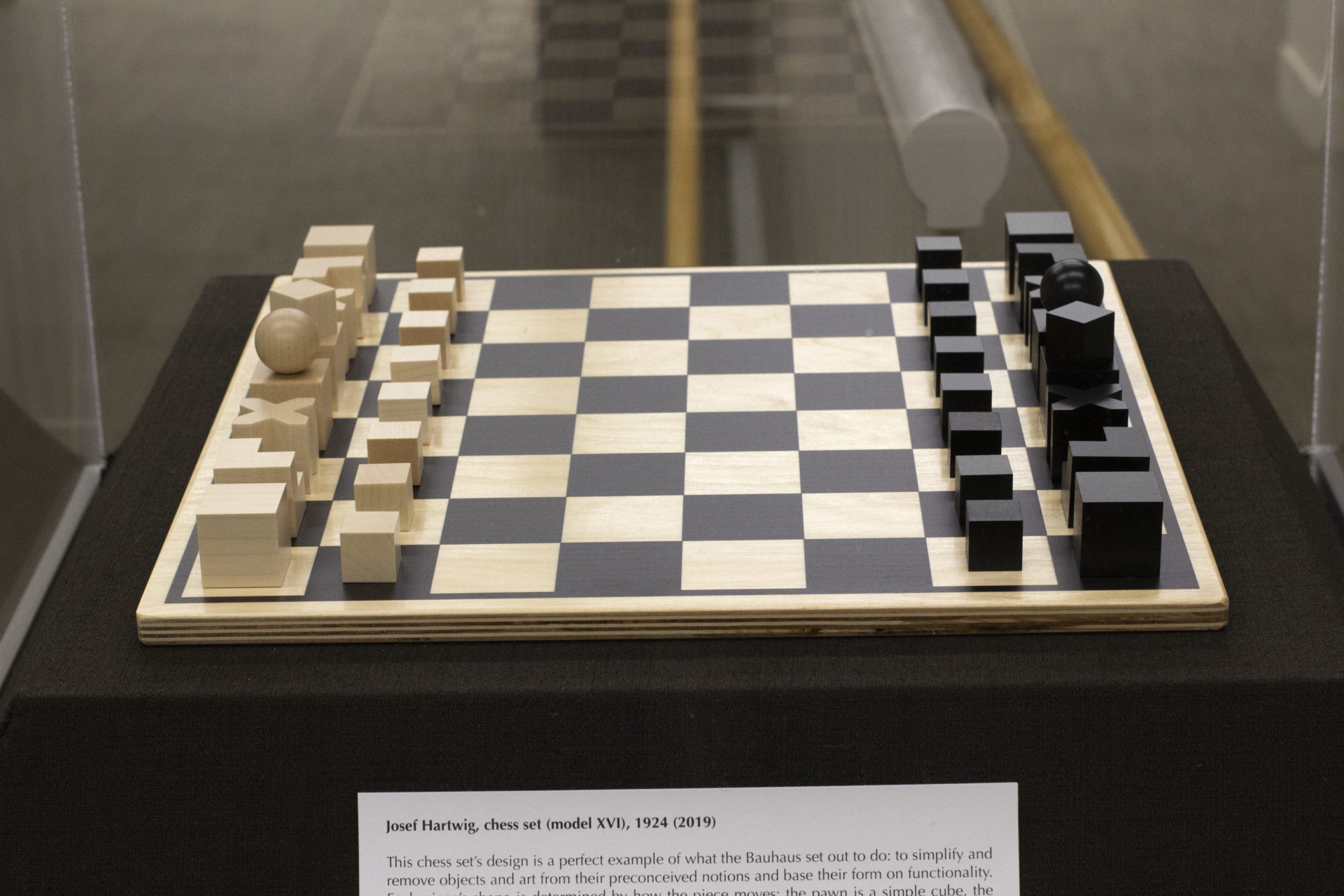

A central theme of the Bauhaus was the feeling that humans were losing control of technology. This was largely a reaction to the devastation that advanced weaponry had caused during world war one. As a result, much of the work at the Bauhaus was aimed at regaining control of technology and using it in the most utilitarian way. This philosophy can be seen in the design of many of the objects featured in the exhibit. For example, the anti-war chess set features pieces whose shapes represent the way that the piece moves rather than its position in war. Another example is the necklaces made of washers, paper clips and silverware by Anni Albers. Members of the LC community had the opportunity to recreate Bauhaus inspired crafts at the reception on Oct. 3.

“I was excited to see how many students stopped by the reception to check out the exhibit, learn about the Bauhaus and try out the Bauhaus-inspired craft projects,” Augst said. “After all, the Bauhaus was a creative and academic community, and its students were not that different from LC students — they were also motivated by the opportunity to learn together, to have interesting experiences and to build a better world.”

Gropius closed down the Bauhaus after 14 years of operation due to consistent pressure from the Nazi regime who labeled the school as a center for Communist intellectualism. The Bauhaus’s ultramodern aesthetic and pedagogical philosophy became hugely influential in the United States and Europe with Gropius becoming a teacher at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in the 1930s. Many Bauhaus students went on to study at Black Mountain College in Black Mountain, North Carolina. Through Harvard, Black Mountain College and the writings of other Bauhaus alumni, the group redefined modernist design throughout the world. Bauhaus designs can be seen in furniture stores like IKEA to this day.

Subscribe to the Mossy Log Newsletter

Stay up to date with the goings-on at Lewis & Clark! Get the top stories or your favorite section delivered to your inbox whenever we release a new issue.

Leave a Reply