Wesleyan University’s newspaper funding slashed unjustly; student publications have the duty to publish opinions from their readership, regardless of their potentially controversial nature

By BRADY ANTONELLI

Part of the liberal arts tradition, or really any college’s goal, is expanding and challenging the beliefs of the student population, a goal which is exemplified by the Opinions section of the school publication. This fall, at Wesleyan University in Middletown Connecticut, the school newspaper budget was cut in the wake of a highly controversial opinion piece, titled “Why Black Lives Matter Isn’t What You Think,” written by a student whose opinion did not imitate those of some of his fellow students. This opinion was not the opinion of the newspaper staff, but the opinion of a single student writer backed by factual evidence, not baseless libel.

From the title of the article, “Why Black Lives Matter Isn’t What You Think,” it is apparent why there was pushback. The student who wrote the article argued that “if vilification and denigration of the police force continues to be a significant portion of Black Lives Matter’s message, then [he] will not support the movement.” He stated that he cannot support a movement that chants that “they want more pigs [police] to fry like bacon.”

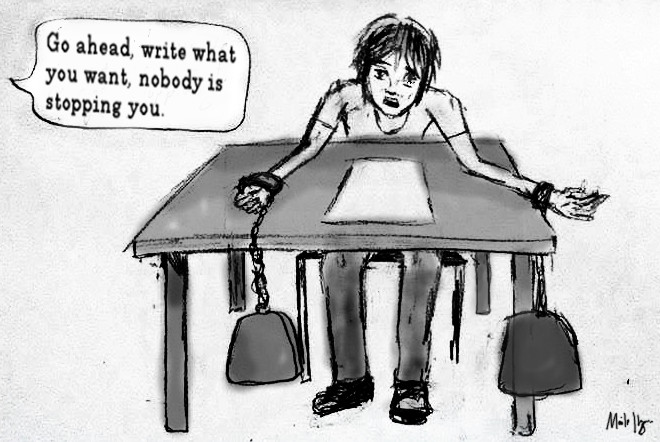

In response to the student outcry that followed, copies of the paper were trashed (there were 3,000 copies printed), the newspaper budget was cut in half and the newspaper was forced to issue an apology. If a school publication, or any other publication for that matter, be it associated with the school or not, publishes the well-researched opinion of one student which does not match the general opinion of its readership, is it the publication’s responsibility to censor that article? Furthermore, is it even within the right of a publication to censor the article?

We, as Americans, are lucky enough live in a country where there is both freedom of press and freedom of speech. These rights are outlined in the First Amendment, and while challenged frequently, the Supreme Court has upheld these rights nearly to their absolutes, except in the case of slander, libel and shouting ‘fire’ in a crowded movie theater, an example of creating unnecessary panic (Schenck vs. United States). Should not the student body, being governed under the same democratic principle of law, enjoy the same freedom from censorship?

One may interject that this is not a national publication. This is a student-run publication at a small liberal arts college, so it does not matter on this scale if the students’ voices are censored so as to not arouse controversy. One could even bring in social contract theory where by attending this school, students tacitly agree to a social contract which forces them to accept the censorship of their press, just as at Lewis & Clark we agree to not having a car on campus for our first year or a two-year on-campus living requirement. Fortunately for us, though, the decision to have a car on campus or to live off-campus is not a question of democracy, it is a question of necessity. Censorship of contentious student opinion is not necessary.

Not only is it unnecessary, it is against the idea of the liberal arts tradition. On college campuses, we should be challenging our prior opinions and welcoming the opinions of others in order to do so, understanding the rationale behind other perspectives, and exploring, learning and working together. If someone’s opinion disagrees with the general opinion, we should find it in ourselves to accept that, and evaluate it as an argument posed by a peer, rather than an enemy. Expressing one’s opinion, especially one backed with evidence, is a right; the fact that the newspaper was punished for this, losing funding and being forced to issue an apology is unfair. In the end it only serves to hurt the many, with a precedent of intolerance of dissention being established. The opinion section of a newspaper should be viewed as a space to freely have the conversations which those who read it feel strongly about.

The press has a right, if not the responsibility, to publish the opinions of everyone, dissenting or congruent. And just as this right is reserved for the press, the readership has the right to not read it, disregard it, or write a response, which, of course, the press has the right to publish.

Subscribe to the Mossy Log Newsletter

Stay up to date with the goings-on at Lewis & Clark! Get the top stories or your favorite section delivered to your inbox whenever we release a new issue.

Leave a Reply