By Julia Stevens /// Staff Writer

On the evening of Feb. 24, students, faculty and visitors made their way to Miller 105 to attend a lecture delivered by internationally recognized professor, author, contemporary art specialist, critical theorist and historian of photography Blake Stimson. In his talk, Stimson compared the work of Allan Sekula, the current visiting photographer in Hoffman Gallery, to the work of defining 20th century modernist photographer Paul Strand. Stimson engaged the audience as he shared personal anecdotes, striking photographs and film clips and powerful quotations. Stimson spoke with confidence and clarity, making the talk not only invaluable but truly captivating.

Stimson began his lecture by presenting his definition of art: a theory plus a feeling. In other words, an artwork presents an idea about the world, and this results in the viewer responding to that idea with an emotion. When Stimson analyzed the photography of Sekula and Strand, he placed an emphasis on the recurring theme of labor. Thus, Stimson was addressing the following question: What emotion does the subject of labor trigger?

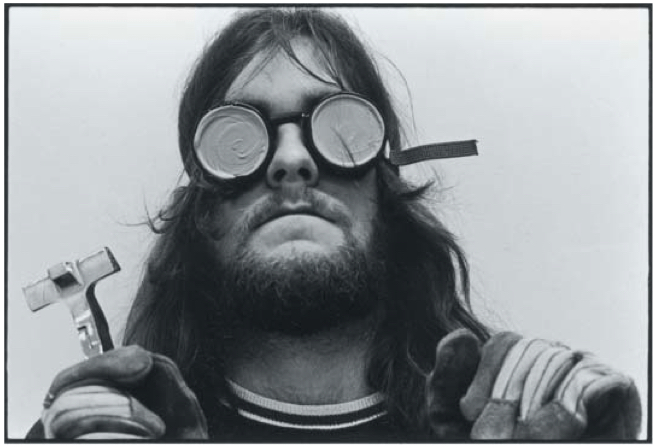

In the lecture, it was made clear that Sekula and Strand present contrasting perspectives of the workforce. Sekula exhibits the vulnerability, suffering and dehumanization that stems from being of the working class. This is seen in his potent film of an impoverished man fishing without a pole, as well as in his performance art piece displaying two employees at a pizzeria bad-mouthing their boss. He addresses the concept that one’s life begins when his or her workday is over.

Strand, on the other hand, presents labor as a necessary function to meet goals. This is displayed in his photo of Mexican filmmakers working together to capture a shot. There is no conflict of labor; they are simply getting the job done. As a result, Strand captures an expression of civil dignity in all of his work.

While these artists differ in many ways, they have one major similarity: They both struggle against the tide by thinking of humans as laborers rather than receivers, which is, refreshingly, an approach that I do not often observe in artwork.

Subscribe to the Mossy Log Newsletter

Stay up to date with the goings-on at Lewis & Clark! Get the top stories or your favorite section delivered to your inbox whenever we release a new issue.

Leave a Reply